Child marriage is defined as ‘a marriage of a girl or boy before the age of 18’, and although both genders experience the phenomenon, it is evident that girls are disproportionately affected.1 Approximately 12 million girls are married during childhood each year, particularly in South Asia.1,2 The literature construes that child marriages are commonly instigated by poverty, a lack of education and societal views amongst various other factors.1 Unfortunately, the consequences of child marriage for the girls involved are both vast and severe. Existing research demonstrates that child marriages increase the incidence of early pregnancies, maternal mortality, school dropout rates and the risk of violence.3–5

Nepal has been classed as one of the worlds’ least developed countries and has a population of approximately 30 million residents.6,7 Child marriages are particularly problematic in Nepal, affecting 33% of girls before the age of 18 and 8% of girls before the age of 15.8 The practice is predominantly witnessed in rural areas, where 83% of the population reside, and many of the causes and consequences are consistent with the reasons mentioned above.9,10 Although Nepal’s legal age for marriage is 20 (or 18 with parental consent), the law is hardly implemented or adhered to.8,11 Nepal’s government has devised a ‘National strategy to end child marriage by 2030’.8 The strategy consists of 6 components, including the need to ‘educate’ and ‘empower’ girls, ‘implement laws and policies’, ‘engage’ men and communities, and ‘strengthen and provide services’.8

Child marriage has a greater impact on the life course of women due to the health implications of pregnancy and dropping out of school.12 According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), child marriages are ‘driven by deep-seated social and religious views’ and are a ‘violation of human and child rights’.1 This research intends to understand the perceptions and attitudes of women in Nepal regarding the impact of child marriage on health. A dearth of qualitative studies currently explore the effect of child marriage on health in Nepal, particularly the health-seeking behaviours of child brides.13 Understanding women’s views is paramount to improve policies, both to prevent the incidence of child marriage in the first place and to deal with the health consequences of those already affected.

Aims and Objectives

This research aims to understand the impact of child marriage on health in Nepal in order to identify methods to improve the implementation of policies in place.

Objectives

-

To identify the determinants of child marriage.

-

To understand how child marriage affects health.

-

To understand the factors which affect the health-seeking behaviour of child brides.

-

To identify ways in which policies regarding child marriage can be improved.

METHODS

Research design

The study employed a qualitative research design to understand the ‘beliefs’ and ‘attitudes’ of those interviewed.14 It has been suggested that qualitative research provides respondents with ‘a voice’ and allows them to talk about aspects of health that may not have been explored before.14

Sampling

Due to time constraints, the study employed a purposive sampling technique, where participants were ‘deliberately’ chosen based on their knowledge and experiences.15 The project host was a representative of the United Nations Development programme, which tackles issues such as child marriage in Nepal. As a result, the host acted as a gatekeeper by identifying suitable participants. Further participants were found by snowballing from the existing respondents in the study.

Inclusion Criteria

-

Being a female

-

Over the age of eighteen and

-

Aware of the issues surrounding child marriage in Nepal

A few of the women interviewed were married as children, but this characteristic was not required for ethical reasons. Females were chosen because of the social norms that drive a disproportionate number of girls into child marriages. The group of thirteen respondents comprised of two doctors, four nurses, five housewives, one agricultural worker and one domestic cleaner. They were aged between twenty-eight and sixty-four, and almost half were educated to university level.

Data collection

Thirteen individual interviews were carried out in May 2019. Semi-structured interviews were adopted as they allowed the interviewer to ‘stray’ from the question guide when necessary.16 The questions used are shown in Appendix 1 in the Online Supplementary Document. Due to the topic’s sensitivity, a vignette was used (Appendix 2 in the Online Supplementary Document). A vignette is a short extract about a ‘hypothetical’ person used to familiarise participants with a topic and set the scene.17 The story permitted the participants to refer to its main character throughout the interview, eliminating the need for them to disclose any personal information.

Seven women from two villages in the Kathmandu valley were interviewed in each village’s communal location. Five health workers were interviewed in a private area of a hospital in Kathmandu, whilst a further health worker was interviewed in a café. Each interview took between 15 and 40 minutes to complete, and all were audio-recorded with consent.

A female translator was chosen to ensure the respondents felt comfortable and to elicit honest answers. She was coached on confidentiality issues, accurate translation and the optional nature of the interviews. A pilot interview ensured that both the translator and the respondents would understand the questions. Three participants spoke fluent English; thus, the translator was only required during ten interviews.

The gatekeeper provided respondents with an information sheet and consent form two days before the interview dates. Consent was also established before each interview and the University of Leeds granted ethical approval.

Data analysis

The lead researcher independently transcribed the audio-recorded data before it was analysed thematically. The transcripts were annotated and coded based on a priori (existing) and emerging themes.15 The transcripts were repeatedly listened to and read throughout the analysis to preserve their meaning while formulating themes. Quotes by participants were organised thematically within a spreadsheet allowing similarities and differences between respondents to be acknowledged. Quotes were included in the report for transparency and to give the reader a sense of the respondent’s voice. They were decided based on their quality and ability to provide extra information.

RESULTS

The findings of this research have been organised based on the objectives they answer. They have been presented thematically and quotes are labelled with their corresponding participant’s unique code.

The perceived causes of child marriage

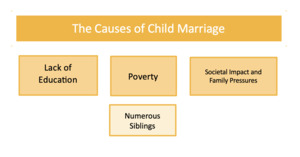

The participants perceived that a lack of education, poverty and societal views were the main drivers of child marriage, as shown in Figure 1.

Lack of education

Most of the participants stated that uneducated girls commonly get married as children. Whilst some suggested that marriage is a direct consequence of being uneducated, others proposed that when a girl or her parents lack education, they are unaware of the consequences.

'Lack of education, they do not know how early marriage will affect their life…’ I12

Poverty and number of siblings

Some participants recognised poverty as a driving factor due to the financial burden of caring for children. One respondent explained that low-income families are likely to have their daughters married if they cannot afford to educate their sons. Others explained that girls with more siblings would be married off to relieve the general and financial responsibilities of having children.

'Because of the difficulties experienced when raising children, children can be married by their parents at the ages of 5-7… It is common when there are many siblings…'I7

Societal views and family pressures

A few participants expressed that getting married at a young age is societally common. One respondent explained that girls are expected to get married and look after their in-laws. Another highlighted the existing opinion that a girl’s real home is at her in-laws.

‘In my time, parents thought that the girls birth home is not her real home…’ I2

The perceived impact of child marriage on health

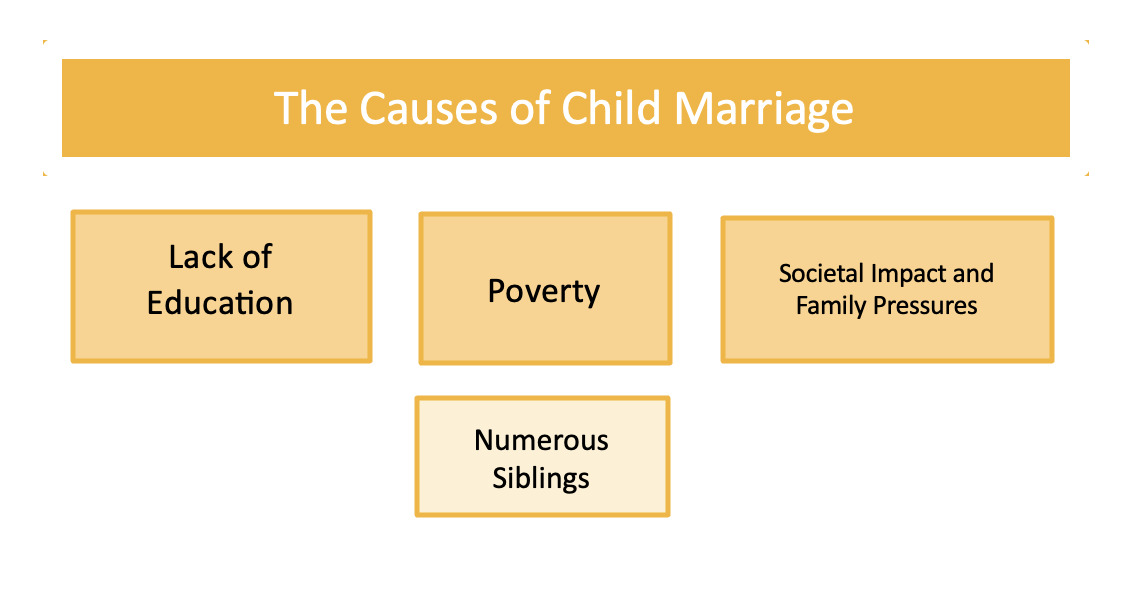

Early pregnancy and pregnancy-related complications, dropping out of school and poor mental health were some of the main themes explored by the participants, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Early pregnancy

The participants identified several causes of early pregnancies. A few of the respondents highlighted that they are pressurised to have children by their parents and in-laws, who want grandchildren. One respondent expressed that this was due to a ‘societal duty.’

Some participants explained that contraception is generally unavailable, particularly in remote areas. This was one of the factors that participants felt increased the incidence of early pregnancies.

'Because of the lack of contraceptives in remote areas, I experienced this as a problem…'I7

In contrast, several participants believed that girls are unaware that contraception exists. Others were concerned that girls are unaware of how pregnancy occurs.

…they are unaware of the contraceptives which are available to them. Therefore, they have intercourse without contraception… I6

One participant stated that young brides are raped if they do not consent to sex.

‘Unwilling girls are raped by their husbands…’ I5

Pregnancy complications

Most of the participants perceived age to account for complications during pregnancy. They expressed that child brides have weak and immature organs, and a few believed that this increases their need for C-sections.

‘… Mothers are unable to force the baby out; therefore C sections are needed…’ I6

A couple of the respondents mentioned uterine complications. One participant explained that uterine prolapse is common amongst child brides due to their age.

Maternal mortality and miscarriages were identified as complications by many of the participants. Maternal mortality was attributed to bleeding, late care seeking and poor facilities. In contrast, miscarriages were perceived to be caused by weak organs and infections.

One participant expressed that child brides often experience post-partum depression. She explained that there is a lack of awareness surrounding the condition and that services are lacking.

'… Post-partum depression is common and is very dangerous because I don’t think we have proper facilities for post-partum depression and counselling because people do not realise it is happening…'I8

One participant stated cervical cancer without elaboration.

School dropout

Several health concerns were raised regarding child brides who drop out of school. Poor or inadequate awareness of hygiene, menstruation and nutrition were worries raised by several participants. They expressed that dropping out of school negatively affects the nutritional and hygienic choices of child brides, both for themselves and their children. It was identified that the children of child brides would also be less educated due to their mother’s lack of knowledge.

…it will also hamper their children because If mothers are educated, their children will be educated….'I8

Only one participant discussed loneliness and the impact on mental health as a consequence of dropping out of school.

'…Being at home can make them feel very lonely. They do not get the chance to communicate with others…'I4

A few respondents reported that child brides are more dependent on their husbands and families when leaving school; this was perceived to give them less power.

Mental health

Many participants explained that young girls are unaware of the realities of married life and are therefore unprepared. This was thought to affect them emotionally.

'During the wedding they are excited that they are getting married to a man, but they do not know about managing a family…'I10

Most of the respondents highlighted that young brides are put under a lot of pressure by their in-laws to work and manage the home. This was perceived to cause stress, and one participant disclosed that she was constantly ‘in fear’ of her in-laws anger as a young bride. One participant identified the societal pressures child brides face to be good mothers.

'…There are societal pressures. For example, people will say, ‘you’re not looking after your children well.’ This affects their mental health…'I6

Some participants highlighted that child brides are often left alone, with unsupportive in-laws and nobody to talk to. Moreover, they explained that mental health is often ignored, and the ability to function is expected within society.

'Usually, they just adapt because that is how they have been bought up. Their mother will have gotten married early. Their sister will have gotten married early, so it’s normal…'I8

Others

Most participants reported that child brides are often victims of domestic violence by their husbands and in-laws. Some suggested this occurs when they do not follow orders or do what is expected. The consequences of domestic violence risk both the physical and mental health of child brides.

‘Young girls do not know how to raise their children and what to feed them; when they do things wrong, violence happens…’

The perceived effect of child marriage on health seeking

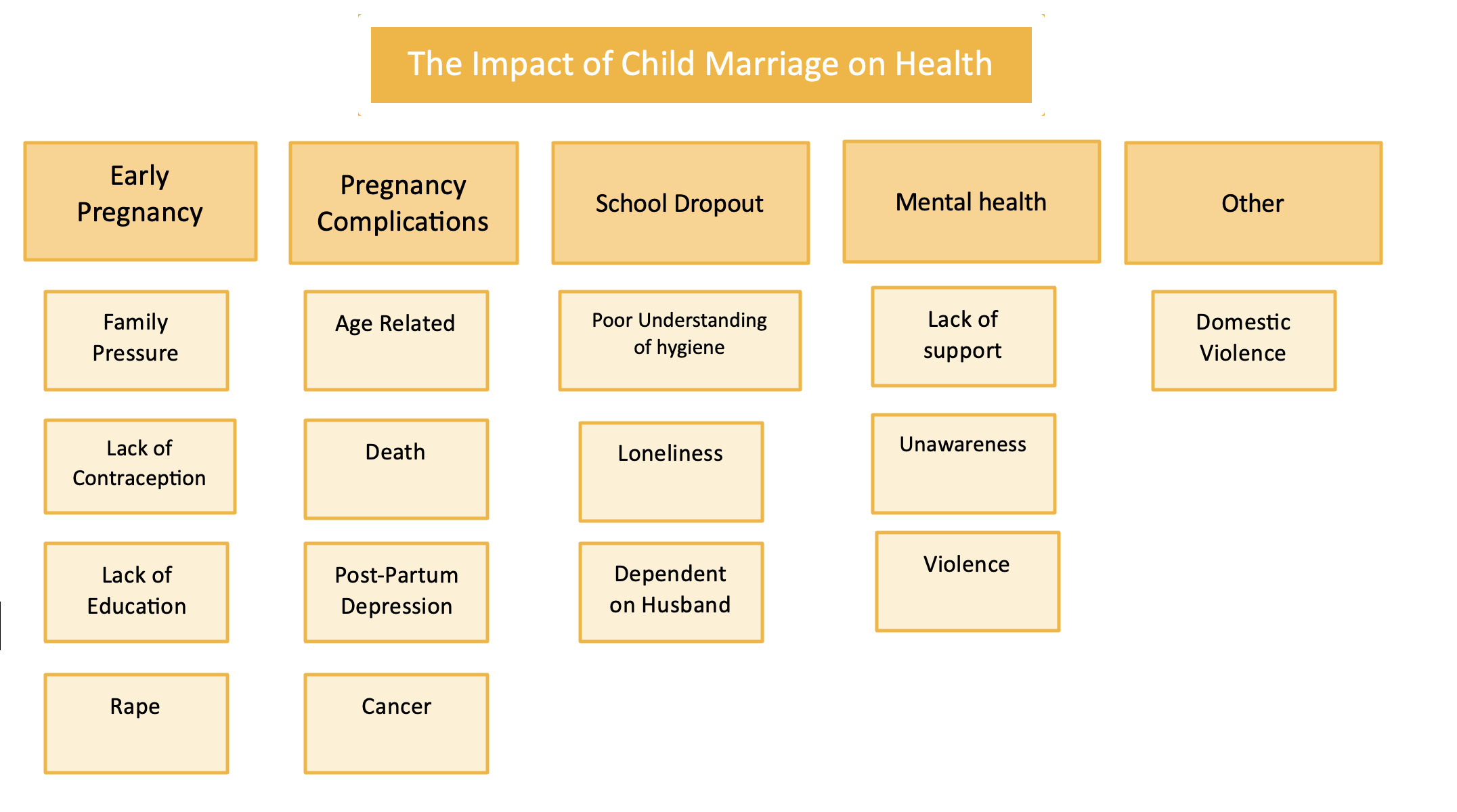

Participants were asked about the factors that influence health seeking in various contexts, such as when seeking contraception, pregnancy-related care, mental healthcare, sexual healthcare and general healthcare by child brides. The perceived factors were awareness, availability, societal factors and a lack of independence as demonstrated in Figure 3.

Awareness

Most of the participants believed that child brides are unaware of contraception, thus, they would not seek it. This was a particular concern within rural areas, though it was felt that some girls in Kathmandu were unaware of contraception. One participant explained that even if child brides knew of contraception, they would not know how to obtain it. Others expressed that girls are afraid of using the contraceptive pill because of misconceptions within society.

'Some girls believe that if they take contraceptives, they could become infertile…'I11

Several participants explained that young brides are unaware of the symptoms of sexually transmitted infections (STI’s) and mental health issues, as such topics are not discussed openly in society. Therefore, young girls do not recognise symptoms as worrying and do not seek care.

‘…they do not understand that they are slowly getting depressed and getting mental diseases…’ I11

Some participants explained that child brides do not know where they can obtain general healthcare.

Availability

A couple of the respondents explained that contraception is generally unavailable, particularly in remote areas. Likewise, one participant identified that doctors are sometimes unavailable to discuss mental health.

In contrast, it was highlighted that girls are likely to seek antenatal care (ANC) because of its wide availability. They explained that outreach programmes exist nationwide, including local health centres in rural areas. Two respondents explained that financial incentives are provided when girls attend ANC 4 times during their pregnancy and when girls deliver at a health facility. This was perceived to improve the uptake of pregnancy-related care.

‘If a girl delivers in a health facility, the girl will get 1500 rupees for a normal delivery and 5000 rupees for a C-section. So, most people tend to come to the hospital and they benefit from it…’ I13

Conversely, one participant identified that gynaecologists and ultrasound scanners are unavailable in some areas of Nepal. Therefore, young girls do not know if they require specialist interventions. A few of the participants felt that the cost of healthcare inhibits health-seeking. Moreover, it was explained that young girls are unlikely to seek mental healthcare until they have a ‘breakdown.’ When asked about sexual health, one respondent explained that girls would wait until their symptoms bothered them.

'They would not seek help until it is actually bothersome. This is at a very late stage…'I8

When probed about general health, a few participants reported that girls would only visit a doctor if their symptoms were severe. One subject explained that girls wait until they are ‘bedridden.’ These findings could be attributed to the cost of healthcare or the stigma surrounding mental and sexual health.

Society

Societal views surrounding mental health were perceived to inhibit girls from seeking care. One participant explained that some families prohibit young brides from discussing mental health issues. Another explained that young girls are unaccepting of these conditions, therefore they do not seek care.

'…society does not accept mentally disturbed people, therefore girls are hesitant to speak about it….'I10

'They do not tell their doctors or anybody else because they think it is a problem of sin…'I12

Seeking care for sexual health problems was also perceived to be inhibited by societal factors. One participant stated that this is due to a lack of trust in healthcare workers to keep their information confidential, especially if they have been promiscuous.

'This is because of the social stigma; they do not trust that their information will be kept confidential…'I13

A few participants identified that in some areas it is societally expected for girls to give birth at home, therefore, care is not sought.

Lack of independence

One participant reported that young brides hesitate to seek care without their husband’s help. Respondents also felt that child brides are shy, particularly around male physicians. Their lack of independence and confidence around male doctors inhibited health-seeking.

Improving Policy

The participants were briefed on the ‘National strategy to end child marriage by 2030’ and its six components. Following this, they were asked how they thought these policies could be revised to improve the health outcomes associated with child marriage. Themes explored by the participants were education, employment, raising awareness and rural outreach.

Education

Most participants believed keeping girls in school is crucial to ending child marriage. While acknowledging the ‘educational’ component of the national strategy, they expressed that more can be done. They explained that education improves independence and allows mothers to educate their children. One participant proposed that child brides should attend night schools to gain independence whilst caring for their families.

'Girls should be kept in school for as long as possible…'I3

Employment

A few of the participants proposed that all women should be employed. One expressed that this would eradicate poverty, simultaneously decreasing the incidence of child marriage. Another explained that employment would ensure their ability to support their families if their husbands passed away.

Awareness

Raising awareness was proposed by some participants. They highlighted that awareness could be raised in communities and within families. Two participants suggested the use of the mass media, such as television adverts.

Rural outreach

Participants suggested that the health facilities in remote areas could be improved so that young girls can obtain care for the complications mentioned previously. One expressed that more doctors need to reach out rurally.

'More health posts should be established in remote areas to ensure that treatment for complications can be obtained…'I3

DISCUSSION

Causes

The reasons for child marriage cited by the participants such as a lack of education, poverty and societal views agree with existing literature.11 The consequences of being uneducated were consistently referred to by the participants indicating the importance of retaining girls in school, a concept widely appreciated by previous research.18 A report by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) found further determinants such as the influence of caste, the dowry system, love marriages and the stigma surrounding pre-marital sex.11 These themes were not identified by this study’s particpants, possibly because they resided in the capital of Nepal, rather than the mainly rural, dalit and indigenous populations interviewed by the HRW.11 Furthermore it is likely that data saturation was not reached given the diverse characteristics of the participants and the comparably lower number of interviews conducted in this study. The participants were not probed which may have limited the answers retrieved.

Impact on health

The participants expressed that early pregnancies may result from an unawareness of contraception; this has been acknowledged previously.11 It should be recognised that lacking awareness limits autonomy, thus child brides must be aware of their options. Rape has not been cited as a cause of early pregnancy before, yet this finding links with a body of evidence that child brides are at an increased risk of experiencing sexual violence.13

Only one participant recalled uterine prolapse as a pregnancy complication experienced by child brides despite the large proportion of health workers in the study sample. Research suggests that the prevalence of this condition lies between 9% and 44% in Nepal.12 It is plausible that this condition and obstetric fistulas were not discussed due to the ‘stigma’ surrounding them or general unawareness.

Literature construes that child brides are at an increased risk of mental health issues,13 yet the reasons why have not been explicitly researched. Pressures to do housework coupled with unrealistic expectations and a lack of support were perceived to be culpable in this study. Therefore, young girls and their parents need to be aware of the realities of married life. Post-partum depression has not previously been cited as a consequence of pregnancy amongst child brides in Nepal before. It was explained that there is a ‘lack of awareness’ surrounding the condition whilst it was generally noted that mental health is often ignored within society, indicating a need for mental health awareness to improve in Nepal.

Health seeking

Shyness was perceived to inhibit seeking care, and one participant expressed that young girls are particularly shy around male doctors. Similar findings were observed by Maharjan et al.13 A study in Nepal by Hayes and Shakya19 identified that most medical students who expressed an interest in working rurally were male, suggesting that there may be a limited number of female doctors where most child brides reside. Therefore, there is a need to ensure that female doctors and health professionals are available to help child brides in rural areas.

The incentives provided by the government to encourage health service use during pregnancy were only mentioned by a couple of the participants, suggesting a possible lack of awareness. Other studies have acknowleged the positive impact of these incentives on health-seeking.13,15 There is a need for the government of Nepal to raise awareness of the programmes that are already in place and to increase their availability.

Policy

Participants suggested strategies such as retaining girls in school and raising awareness. In Bara, a district of Nepal, ‘children’s clubs’ were set up to keep children in school whilst raising awareness of the issues surrounding child marriage.20 As a result, numerous villages in the district were confirmed as ‘child-marriage free zones,’ demonstrating its success.

Other suggestions by participants included the employment of women and improving rural health facilities; these have been proposed within the literature.13,21

Limitations

The vignette was rarely referred to by the participants being interviewed. It is possible that the sensitive nature of the topics addressed could have been discussed in greater detail if the vignette had been utilised more. However, it was evident that the vignette enforced strong emotions within the participants, and they were eager to share their personal experiences after hearing the short extract.

Many participants held back when answering questions regarding mental health, sexual health and violence. They explained they felt shy discussing these topics, and due to their hesitancy, they were not probed further.

As the question guide was based on existing literature, there is a possibility that the questions were leading. However, open questions were asked in each interview section to avoid this.

The research occurred in the Kathmandu valley, yet most child marriages occur rurally. Although many of the participants had either visited or were from remote areas, alternative themes could likely have been elicited from a cohort of rural women.

Approximately twenty individuals were invited for interview, of which thirteen took part. Very few new themes were elicited in the latter half of interviews, therefore it could be presumed that the most common themes were discussed. Despite this, it is unlikely that data saturation was reached given the variety of ages, occupations and educational achievements of the study cohort. More themes may have been retrieved from community leaders and teachers who work closely with young people.

Validation techniques such as respondent validation and triangulation did not occur due to time constraints. These techniques would have increased the reliability of the results.15 It should also be considered that the lead researcher analysed all data independently, and therefore research bias is a possibility.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the main factors perceived to drive young girls into early marriages were a lack of education, poverty and societal norms. The participants agreed that early pregnancies are common and complications result from age. Most participants recognised that young brides drop out of school once married or pregnant. This was believed to affect their independence and their ability to make health-related decisions. The practice was perceived to have a negative impact on mental health, and some felt it increased the risk of violence. The participants explained that health-seeking is inhibited by unawareness of symptoms and available help, societal views and a lack of independence. Conversely, incentives were believed to improve health-seeking. Educating girls and employing women would reduce the incidence of child mariage. This underscores the need to raise awareness and improve rural support. Further research could delve into the the views of boys and men in the most affected areas of Nepal, to aid current understanding of why child marriage occurs and the societal views which still exist.

Acknowledgements

The support of the United Nations Development Programme in Kathmandu, for their help in organising data collection. The support of the author’s supervisor at the Nuffield Centre for International Health. The support of the translator whilst in Nepal.

Disclaimer

This report has been submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a degree at the University of Leeds. The statements and opinions presented within are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, or the University of Leeds

Ethics statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Ethical approval was granted by the Leeds Institute of Health Sciences Research Ethics Sub-Committee (FMHREC-18-1.3).

Funding

None

Authorship contributions

RS is the only author.

Disclosure of interest

The authors completed the ICMJE Disclosure of Interest Form (available upon request from the corresponding author) and disclose no relevant interests.

Additional material

Please refer to the Online Supplementary Material

Correspondence to:

Reena Seta

University of Leeds, United Kingdom

[email protected]