Medical education in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) can present a set of challenges that are different from those in high-income countries. Inadequate funding for national education programs, inconsistent health system infrastructures, and traditionalist views of the medical instructor-trainee relationship are all factors that can limit the efficacy of medical education.1–3 These elements, when present within the context of ongoing violent conflict and instability, and a subsequent exodus of medical professionals, can have a devastating effect on the current and future medical education in that country. Unfortunately, the 10+ year war in Afghanistan has led to increased need for surgical services, an inadequate and overworked staff, and a “brain drain” of qualified anesthesiologists.4 In 2010, the World Health Organization estimated that there were only nine physician anesthetists for the Afghan population of 32 million.5 Moreover, the majority of these anesthesiologists practice in larger regional or national medical centers; anesthesia services in rural areas are usually delivered by nurses and anesthesia technicians. A recent survey conducted at Afghan regional, provincial, and district hospitals found that 63% of the district and provincial hospitals did not have a functioning anesthesia machine, and 41% did not have the capacity to provide regional anesthesia of any type.6 Furthermore, physician anesthesiologists were present in only 30% of facilities.6 Expanding and strengthening the anesthesia workforce in Afghanistan is critical to improving the quality and sustainability of anesthesia services throughout the country. To do this requires attention on multiple complex factors including future workforce development, and strengthening the expertise of faculty educating these students. Short courses are interventions that hold potential to positively influence this long-term need through short-term efforts to strengthen faculty expertise, technically and pedagogically. Short-courses have been utilized to prepare health care professionals in numerous LMIC settings, and have been shown to improve knowledge among learners.7–9 In the context of LMICs, appropriately designed short courses that take into account the existing national education infrastructure and resources, provide a framework for measurable outcomes, and build sustainable relationships with local staff, are poised to yield short- and long-term educational and practical impact. Instructional design, the process by which formalized learning theory is incorporated into education planning, is another tool that, when incorporated into short course implementation, can further improve learning.10 At its core, instructional design is the systematic development of instructional specifications. It relies on learning theories and pedagogical models to elevate the relevance, impact and quality of instruction. Effective instructional design is iterative and involves11:

-

Identification and analysis of the educational requirements

-

Development of specific, measurable objectives

-

Development of components aimed at achieving objectives

-

Combination of components into one curriculum

-

Delivery of curriculum

-

Evaluation of impact

Methods such as the flipped classroom, learning-by-teaching, and open communication, when designed into the curriculum, have been shown to have a positive impact on medical knowledge retention and comprehension.12–14 However, in many LMICs (including Afghanistan), educational strategies continue to rely heavily on traditional lecture formats, where content delivery and knowledge transmission take primacy resulting in a hierarchical and unilateral exchange of information in a large group setting, without much opportunity for discussion or active learning. The use of a short course grounded in promising instructional design principles and incorporating various active learning techniques could have a significant impact on knowledge gain among Afghan anesthesiologists. This study sought to identify the feasibility and potential immediate educational impact of a newly designed regional anesthesia short-course by assessing knowledge gain and learner opinions of the course.

METHODS

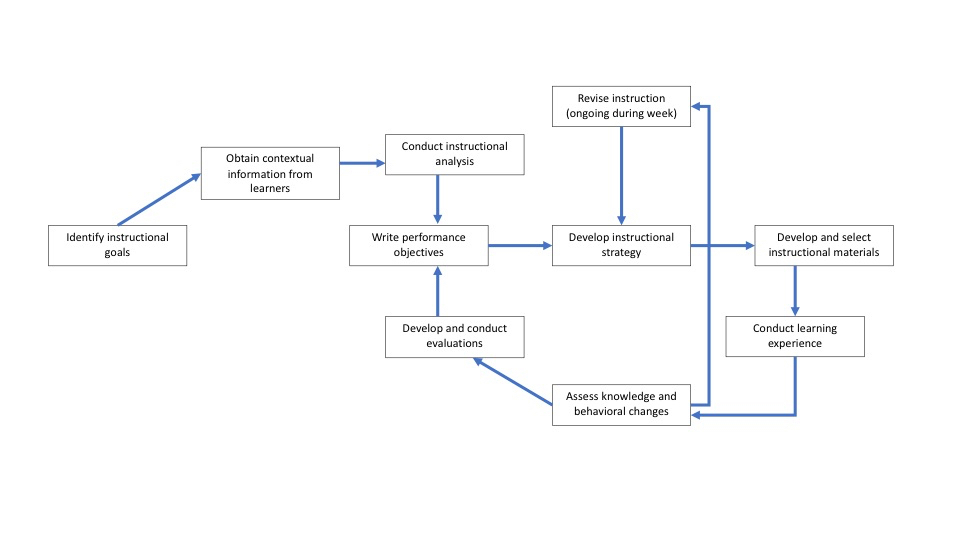

This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB); requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB. The short course was instituted as part of an ongoing multilateral project between the University of Minnesota (UMN) and Kabul University of Medical Sciences (KUMS). The UMN partnership with KUMS is part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Afghanistan University Support and Workforce Development Program (USWDP) – a five-year project that aimed to increase the skills and employability of professionally qualified Afghan men and women in the public and private sectors. During the project timespan, quarterly weeklong in-person educational sessions were conducted to achieve work plan objectives as identified collaboratively by KUMS and UMN faculty. In 2018, perioperative pain was identified by the project stakeholders as an important educational topic for their faculty. Using instructional design principles, two United States (US)-based anesthesiology faculty developed a week-long short course for Afghan faculty. The US faculty expected that by the conclusion of the short course, Afghan faculty learners would be able to 1) identify basic elements of safety in regional anesthesia, 2) list some common nerve blocks that would be useful in their practice and describe the techniques, 3) discuss the principles of perioperative pain management and 4) explain how to incorporate instructional design principles into their own teaching. The instructional design plan followed the Dick and Carey model,11 where the educational strategy includes the use of objective sharing, structured evaluation, constructive feedback, and ongoing revision (see Figure 1). Flipped classroom, simulation, workshops, game theory, and learning-by-teaching methodologies were incorporated into the planned learning sessions (see Figure 2). Learning objectives, along with prereading materials, were electronically delivered to the learners prior to the beginning of the course.

From August 6 to August 11, 2018, eight anesthesiology faculty from KUMS participated in the educational program in Bangalore, India. Experience in teaching among participating KUMS faculty ranged from less than 5 years to more than twenty years. All faculty considered themselves inexperienced with regional anesthesia. During the 6-day course, learners participated in didactics and workshops discussing regional anesthesia techniques, multimodal analgesia, safety, pain assessment and management, and the influence of ethno-cultural context on pain control. A total of six didactic sessions, three workshops, three learning-by-teaching, two game sessions, and three simulations were held. Additionally, the learners participated in instructional design workshops in an effort to build and practice effective teaching skills they could use in their classrooms in Afghanistan. Dari / English interpreters were present for all sessions.

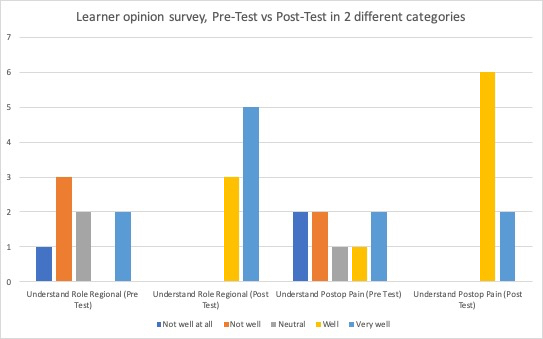

Knowledge gain from the short course was assessed using US faculty-developed multiple choice pretests and posttests. These tests were written in English and given to all participants; Dari interpreters were immediately available during testing to ensure understanding of the questions. Opinion surveys regarding regional anesthesia and the utility of the course were also completed. The opinion surveys asked the learners to classify their answers to the following questions as ‘not well at all,’ ‘not well,’ ‘neutral,’ ‘well,’ or ‘very well’:

-

How well would you say you understand the role and scope of regional anesthetic techniques?

-

How well would you say you understand how to assess and treat patients’ postoperative pain?

Additionally, at the conclusion of the course, the learners were asked the degree, on a scale of 1 to 5, to which they strongly agreed (5) or strongly disagreed (1) that the course had improved their ability to use instructional design principles in specific aspects of their own teaching.

RESULTS

All learners completed the course with full participation. A median of 5 out of 10 questions were answered correctly by the learners on the pretest; this score improved to a median of 6.5 on the posttest (Figure 3). The number of learners who described understanding “very well” the role of regional anesthesia in their perioperative care practice increased from 2 to 5 faculty (Figure 4). Likewise, the number of learners who described their understanding of postoperative pain and their ability to perform regional anesthesia as “not well at all” decreased from 2 to 0 in both categories. At the conclusion of the week, 7 out of 8 learners classified the regional anesthesia and pain education program as “very useful” to their practice.

Regarding instructional design, the majority of participants strongly agreed that at the conclusion of the course, they had improved their abilities to 1) redesign lessons based on backward design principles, 2) design assessments that are aligned to course objectives, and 3) integrate active learning strategies within existing courses (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The pilot multi-institutional short course appears to have improved the knowledge base of the Afghan faculty participants. While a median gain of 30% may be modest, we believe it to be significant given the small number of learners, the relatively short time span involved, and the highly technical nature of the topics covered. Other short courses, some as brief as several one-hour sessions, have been shown to increase knowledge and/or technical ability by as much as 44%.8,15,16 Thus, we believe the improvement in knowledge as demonstrated in the post-intervention testing is in accord with other those of other interventions in LMIC settings. The knowledge increase is also supported by the learners’ increased confidence in their understanding of the role of regional anesthesia and their ability to assess and treat pain. To our knowledge, this is the first project examining the outcomes of a regional anesthesia and acute pain management short course delivered to Afghan anesthesiologists.

With regard to the instructional design of the short course, several characteristics may have contributed to its success:

Pragmatic Curriculum Development

During the planning stages of this intervention, the input of the Afghan learners was critical to the development of an appropriate curriculum and tangible learning objectives. KUMS faculty were polled regarding resource availability, access to the internet, previous exposure to regional anesthesia concepts, and current clinical practices (including current analgesic modalities). Their familiarity with instructional design theory and practice in teaching was assessed, as was their usual educational environment. This information allowed US-based faculty to tailor the short-course to maximize applicability of the educational material to the Afghan learners’ context.

Flipped-Classroom

Flipped classroom theory is based on the premise that learners will have access to and utilize learning materials prior to the educational session and thus the didactic time can be devoted to discussion or other active learning methods.13 For the KUMS/UMN short course, learners completed a number of pre-reading assignments which enabled faculty to focus classroom discussion and activities on those items and concepts deemed most challenging by learners.

Active Learning

Simulations, workshops, and games, when utilized as agents of active learning, have been shown to be effective for medical education.17–20 The use of these methods was well-received by the learners, who were not usually exposed to these techniques in their home context.

Small Group of Learners

Similarly, the small group of learners involved likely contributed to the learners’ increase in knowledge. Previous short courses on a variety of topics have been shown to be effective with small groups of learners. Although speculative, the small number of learners may enhance the learning process by facilitating active learning, enabling open and detailed discussion, and increasing workshop participation.

Learning by Teaching

Teaching appears to provide a reliable avenue for learning. Within the context of medical education, residents who teach have greater knowledge acquisition and self-report improved clinical skills compared to learners who only attend lectures.21–24 The integration of teaching for KUMS faculty in this study served two purposes: 1) To facilitate learning of the educational material, and 2) to improve the teaching skills of the Afghan participants in an informal manner.

Mutuality and Continuity

A particular benefit of this short course is that it was part of a larger longitudinal project over a two-year period with approximately quarterly in-person meetings. The key project leaders and participants remained largely the same throughout, and project goals were developed mutually. The relationships and knowledge developed over this time likely contributed to the success of this exchange. These characteristics of mutuality and continuity have been identified as pillars of success in development efforts.25 In this vein, after the conclusion of the short-course, US faculty continued to engage the Afghan participants with future workshops.

Limitations

The most significant limitation in our project is the reliance on one-group post-tests to assess educational impact. This one-group quasi-experimental approach lacks a control group and inherently exposes the results of our study to participant bias and placebo effect. However, we believe this bias was unavoidable because the use of a control group would not have been practical nor ethical within the goals of project. Ideally educational gains would be assessed using another methodology such as critical thinking problem-solving or clinical skills evaluation. However, three logistical barriers existed for this approach. First, reliable internet access was a challenge for learners once they returned to Afghanistan. While some preceding coursework was able to be done by the learners, frequent and reliable access to electronic educational materials was at times not possible. Therefore, assessment of knowledge retention after the short course via electronic means would not provide the reliability and accuracy required for effective measurement. Second, each subsequent quarterly learning session’s schedule was eventful and devoted to other topics, precluding the devotion of time and resources for assessment of this specific analgesia-focused short course. Third, security concerns prevented US faculty from travelling to Afghanistan. Thus, direct observation of concept application within clinical and academic practice was not possible. Consequently, our project did not allow for long-term follow-up of faculty behaviors upon return to practice and teaching in Afghanistan. Future studies could implement and evaluate adequately powered short-course interventions with longitudinal follow-up assessments, including assessing changes in participants’ behaviors in clinical practice or teaching environments.

Practically, the language barriers required the use of interpreters, which was a limitation, not on the study design per se, but on the implementation of the short course. While the interpreters had relevant medical backgrounds, occasional technical concepts would be unfamiliar to them and may have contributed to possible translation bias.

The nature of this project, and the relatively small number of Afghan faculty available to participate, limit the generalizability of our study findings. While study findings could be valuable to others engaged in international workforce development projects, our findings should be cautiously applied to other contexts, and done so with an appreciation for the unique dynamics of every partnership and the underlying relationship and trust-building that make partnerships such as this one successful. Similarly, the small number of participants unfortunately prevented a statistical analysis of the outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

The short course in regional anesthesia and pain management was well-accepted and appeared to improve knowledge and confidence among Afghan faculty participants. Additionally, Afghan faculty developed an increased understanding of, and appreciation for, instructional design best practices they could implement. The results of this pilot project suggest that short courses based in instructional design can be feasible and useful and effective in an LMIC setting such as Afghanistan, with critical and difficult medical concepts and techniques. Short courses, in the absence of long-term investment opportunities, may be critical development strategies for both higher education workforce development and the advancement of health care providers entering the Afghan healthcare workforce. Further investigations into the use of short courses in this context are warranted.

Acknowledgments: This manuscript is made possible by the support of USAID and FHI 360 through award number AID-306-A-13-00009. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the US Government, or FHI360. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank the participating KUMS faculty for their engagement during the educational effort and thank the Dari interpreters for their linguistic contributions during the educational sessions. This report was previously presented, in part, at the American Society of Regional Anesthesia Annual Meeting (April 2019, Las Vegas, NV).

Ethics: This report does not describe human research. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined this educational program to be IRB exempt. Requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Funding: USAID and FHI 360 through award number AID-306-A-13-00009.

Authorship contributions: All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study, analysis of the data, and writing of the manuscript

Competing interests: Competing interests: The authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding to:

Alberto E. Ardon MD MPH

Mayo Clinic

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine

4500 San Pablo Rd S

Jacksonville, FL 32224

[email protected]