Nepal, a multi-ethnic country, is located in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) South-East Asia region and is landlocked by China and India. According to the World Bank, Nepal is a low-income economy. 1

Nepal’s population of 29 million has an average life expectancy of 69 for men and 72 years for women. 2 This is a stark contrast to high-income countries like the UK, where men and women are expected to reach 80 and 83 respectively. 3

Mental health in Nepal

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as:

“A state of well-being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community”. 4

Globally, poor mental health is a serious public health concern. 80 per cent of people with severe mental illness in Low and-Middle Income Countries receive no effective treatment. 5 This is especially relevant in Nepal, where there are limited mental health specialists. For comparison, there are only 0.36 psychiatrists per 100,000 in Nepal compared to 10.54 in the United States of America. 6,7 Furthermore, mental health is highly stigmatized in Nepal and this acts as a major barrier for seeking mental health care. 5 This is concerning considering Nepal had the seventh highest global suicide rate in 2014. 8 Subsequently, Nepal is failing to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 3, “Good health and wellbeing”. 9

Dalits and mental health

In Nepal, caste-based disparities have been identified in mental health. 10 The caste system in Nepal is rooted in the India-varna system, which divides society into rankings based on ancestral lineages. 11 Within this, the Dalit caste is the lowest, as seen in Figure 1.

Dalits comprise an estimated 20 per cent of Nepal’s population. 12 The term “Dalit” only came into usage in Nepal after 1990 and refers to those considered “untouchable”. 13,14 Dalits have the poorest life-expectancies, incomes, literacy rates and job prospects, making them the most disadvantaged and discriminated against in Nepali society. 12 This is despite Nepal’s constitution declaring that everyone is equal regardless of caste or tribe. 15

Kohrt et al., found that Dalits have a considerably greater prevalence of depression and anxiety when compared with higher castes. 10 This is unsurprising considering the discrimination and poverty that Dalits endure. Exploring relationships between caste and mental health has received little research attention. 10 Therefore, it is important to investigate Dalits’ experiences of mental illness, the barriers faced when trying to access support and to identify possible causes of stigma. Investigating this should help inform anti-stigma policies and develop interventions to better support mental health within the community.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

This study aims to explore the causes and experiences of mental health stigma among the Dalit community and the barriers to mental health support in Kathmandu. This is guided by the following objectives:

-

To explore Dalits perceptions of mental health in Kathmandu

-

To discuss the impact of mental health stigmatization within the Dalit community in Kathmandu

-

To explore the barriers that prevent Dalits from receiving mental health support in Kathmandu

-

To identify possible causes of the stigma associated with mental health within the Dalit community in Kathmandu

METHODS

Research design

The research was undertaken through the Ric-Rose Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) in urban Gothatar, Kathmandu. A qualitative cross-sectional approach was chosen to elicit maximum information and to investigate the ‘how’ and ‘why’ behind the mental health stigma. 16 Individual semi-structured interviews (SSIs) were used to accommodate for unexpected emerging themes. 17 The question guide, found in Appendix 1 in the Online Supplementary Material, was self-developed and adapted from similar studies from the literature that also used SSI’s. 18,19 The process of formulating the questions was based on recommendations from Bryman, as demonstrated in Figure 2. 20

Sampling

The host arranged for a Dalit community leader to act as the gatekeeper for recruitment. The gatekeeper had previously worked alongside the host in well-being programs, meaning they understood the research topic and could accurately inform participants about the project. Purposive sampling was deemed suitable to best identify related informative-rich cases. 21 Some participants were recruited conveniently through snowballing from previous participants. 10 participants were Dalits and two were Brahmin caste social workers from the NGO who worked alongside Dalits. During the fieldwork, the decision was made to include the Brahmin social workers in the research after discovering their unique insight on mental health in the Dalit community. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Data collection

A pilot guide was trialled with the host who was fluent in both English and Nepali, enabling the guide to be validated on the native tongue. Following this, questions were added, and phrases adjusted to ensure the questions translated appropriately. Seven of the interviews were conducted at the NGO’s premises whilst five were conducted in the gatekeeper’s house.

An interpreter, who was trained on confidentiality and taking informed consent, was used for eight interviews. The interpreter was also trained on the interview guide and the necessity for direct interpretation between the researcher and participants. All participants were briefed on the research at least six hours prior to the interviews due to the topic’s sensitivity. Preceding the interviews, participants were taken through the information sheets and consent forms (Appendix 1 and 2 in the Online Supplementary Material). Ethical approval was granted by The University of Leeds and covered by the Ric-Rose’s in-country ethical approval.

Interviews were conducted according to the question guide in Appendix 3 in the Online Supplementary Material and lasted 20-40 minutes. All participants gave signed informed consent including audio-recording. Each written informed consent form was assigned a pseudonym which corresponded to a participant’s transcript, to maintain anonymity and confidentiality. All participants were offered tea and biscuits and reimbursed for their travel costs except the social workers.

Data analysis

The audio-data was transcribed naturistically to enrich data collection. 22 Relevant non-verbal cues were added to capture signals that alter meaning. Transcripts were read through and colour coded to highlight a priori codes. To explore unanticipated ideas, transcripts were re-read for familiarization and annotated with emerging themes. Table 2 identifies which codes were a priori or emerging codes.

Recommendations from Ryan and Bernard were adopted when identifying emerging themes such as looking for repetitions, contradictions and indigenous categories. 23 These codes were then compiled into a “Thematic Framework” in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc, Seattle WA, USA) to allow for content analysis. 20 Thematic analysis was used due to its flexibility and potential to provide detailed interpretation. 20 Throughout the analysis, themes were adjusted accordingly and referred back to the original transcripts through an iterative process.

RESULTS

The objectives are discussed according to the themes highlighted through thematic analysis, as demonstrated in Table 2.

Perceptions of mental health

To gain a broader perspective of participants’ perceptions of mental health, interviewees were first asked to explain how people with mental illness are viewed in the Dalit community. Common sub-themes that surfaced from this discussion are demonstrated in Figure 3 and include; failure to perceive mental health as a real illness, perceiving it to be incurable, its association with addiction, alongside being labelled as Pāgala.

Not a real illness

When discussing how Dalits perceived mental health, common views expressed were that mental health is not seen as a real illness within their community. Moreover, several participants did not recognise mental illness as a disease that needs treating by a doctor. Another perception commonly held among the interviewees was that mental health is a “behavioural problem” instead of a “biochemical” or “medical problem”.

Incurable

On the other hand, some participants felt that poor mental health was a disease, and that it was ‘incurable’. When asked to expand on the word ‘incurable’, one participant explained that even if a person’s mental health condition could be cured, that their reputation would remain forever stained.

Pāgala

A Nepali term frequently mentioned within the interviews when discussing mental health was “Pāgala”, meaning “mad”. Many participants said the word with apparent disdain which demonstrated the deep-seated negative perspectives of mental health among the Dalit community.

Drugs and alcohol

Several participants associated the topic of mental health with alcoholism and drugs. Some participants believed drugs and alcohol to be the cause of mental health problems, whilst others discussed substance use as a coping mechanism ‘to self-treat’ their mental health problems. For example, one participant discussed how their husband used marijuana, which is illegal in Nepal, as a coping mechanism to “self-medicate his depression”. 24

Alternatively, other participants explained that they thought consuming alcohol and drugs was a mental health condition in itself. This was discussed in relation to caste-based discrimination and how it can cause Dalits to turn to substance abuse and become alcoholics. A cultural explanation was offered by one interviewee as to why Dalits have problems with alcohol and drugs. This interviewee explained that Shiva the God smokes weed and another goddess drinks wine. Therefore, when they visit the temples, they give one glass to the gods and drink the rest of the wine. This justification was used to make heavy alcohol consumption “culturally acceptable”.

An alternative link to mental health and alcoholism was revealed by one participant who disclosed that corrupt politicians use alcohol as a means of manipulating Dalits. The process in which this happens was then explained:

“Rich politicians give the Dalits free alcohol and then force them off their own land in return as payment. This has meant many are homeless”.

Following this, a discussion ensued on how homelessness among Dalits often perpetuates further mental health problems and addiction.

Impact of mental health stigmatization

Participants were asked how people with mental health conditions are treated within the Dalit community. Common sub-themes that arose from this discussion included being outcast and homeless alongside gender differences. These key themes are demonstrated in Figure 4.

Outcast and homeless

A theme reiterated by participants was that the Dalit community ‘outcastes’ and ‘boycotts’ people with mental health conditions and consequently avoids confronting the topic. A reason suggested for this by interviewees was that Dalit communities do not trust individuals with poor mental health. Moreover, multiple participants mentioned the family’s part in rejecting relatives with mental health conditions, specifically when discussing schizophrenia and depression. A reason listed for this is that family members don’t want mentally unwell people in the house as "they worry they will cause problems". Resultantly, they outcast people out of fear of “losing prestige”. The exclusion of people with mental health conditions was also discussed in relation to work. Interviewees identified that both the stigma of being a Dalit and having a mental health issue prevents people from employing their services which can impact upon their businesses.

Gender differences

Numerous participants mentioned how the impact of stigma varies between genders. Some participants expressed the opinion that women receive more stigma for mental health conditions because this discrimination compounds the existing gender-based discrimination towards women in Nepal. This opinion was echoed by another participant who explained that mental illness is a bigger problem for women in their community. Two participants stated that when a Dalit family rejects a female relative with mental health conditions, it is more problematic due to the increased vulnerability of women to exploitation, “abuse and rape”.

Contrastingly, one participant stated the impact of mental health stigma is similar for the genders:

“I don’t think there are many gender differences because both genders are discriminated”.

This participant went on to explain that both herself and her husband had experienced comparable discrimination for their mental health conditions and had been outcast from their community by their neighbours.

Barriers to support

The main reported barriers to obtaining mental health support included financial burdens, a lack of awareness and limited services, as demonstrated by Figure 5. Some participants went on to share their opinions on how these barriers can be tackled.

Financial

Economic pressures were mentioned as a barrier to seeking mental health support by numerous participants. In some interviews, the price of medication was discussed as being the primary barrier, whilst others could not afford the consultation fee to obtain a diagnosis. This economic burden was reiterated by the social worker who stated that:

"People are hopeless as their community is being taken advantage of by the government and being cheated off their land".

This quote concurs with the aforementioned corruption in relation to alcoholism, whereby Dalits are being forced off their own land.

Awareness

A key barrier reported by numerous participants was awareness. One interviewee summarised this by stating:

“There is no awareness of mental health or support or education on the matter”.

Some participants said they were unaware of where to seek help, whilst others were unaware that mental health conditions even existed.

Availability of services

A key barrier to obtaining support discussed was the lack of available mental health services. For example, one respondent explained that there were no recovery programs in their community for mental health care and addiction support. Another participant discussed how belonging to such an isolated and discriminated community restricts access to support from outside. Another interviewee explained that obtaining a formal diagnosis “so knowing something is wrong in the first place” was a major barrier to initiating support.

Overcoming barriers

Tackling stigmatisation and the barriers to mental health support were discussed with some of the participants and the majority of the responses focused on educating the next generation. One of the participants from the newer generation of Dalits believed that their generation could change this stigma about mental health, both "towards our community and within the community". They explained that better education will lead to less discrimination.

An alternative perspective highlighted was that community mental health education might face some resistance as it neglects to solve the issues many Dalits deem most important, such as employment. This participant thought that some community members would believe that awareness will not “give us jobs or solve our problems”. Another participant suggested tackling the Dalit community’s alcoholism as a means of improving mental health; “We also need to stop drinking as a community”.

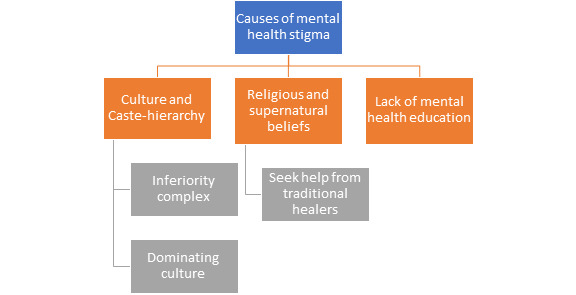

Causes of mental health stigma

All participants were asked what they thought caused the stigma surrounding mental health in the Dalit community. Respondents mentioned religious or supernatural causes, the influence of caste and culture alongside a lack of education, which are highlighted in Figure 6.

Religious and supernatural

When asked what causes the stigma towards mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and schizophrenia, numerous participants said it originated from the community’s widely held supernatural and superstitious beliefs. A few participants explained that the older generation raised their children to think that "being mentally ill is related to gods, demons and karma". It is these supernatural beliefs that directly influence the community’s rejection of medical doctors when mental health is concerned. They explained that Dalits choose “traditional spiritual headers over hospital doctors” as they are unaware that mental illness could be related to biology.

Culture and caste

Another cause of mental health stigma discussed was culture. This was debated in relation to the caste system and its complex influences on Dalits. One respondent plainly said that the culture among Dalits does not accept mental health. Another interviewee suggested that the preconceptions and prejudices associated with Dalits and addiction enhance the stigmatisation related to mental health;

“Any stigma based on being an alcoholic compounds mental health stigma as people think it’s normal for Dalits to have addictions”.

When discussing how the Dalit culture can contribute to mental health stigma, two different forms were identified. One form was the stigma and domination that Dalits feel directed at them externally from other castes. They explained how this causes an “inferiority complex”, which exacerbates poor mental health. Another participant said that “We are raised with the psychology to believe we are lower”, which highlights the other form of stigma which comes from within the caste. In contrast, another participant rejected this belief and instead felt that all Dalits should be encouraged to achieve and believe they are equal. They boldly said,

“At the end of the day, we are all human, so caste shouldn’t matter”.

Lack of education

Only one out of the 10 Dalit participants had received any formal mental health education, which was during their sociology degree. Many participants reiterated this;

"We are taught a lot about physical health in school but nothing about mental health".

Participants explained that this leads to people growing up with the belief that mental health is not as important as physical health and they “don’t know to look for symptoms”.

DISCUSSION

Implications of findings

Mental health among Dalits is perceived as an incurable, unreal disease associated with addiction and madness. The causes of mental health stigma were found to stem from religion, supernatural teachings, culture, caste and a lack of education. Experiences of mental health stigma among the Dalit community varied extensively but common experiences shared related to homelessness, family exclusion, vulnerability and exploitation. Barriers identified that prevent Dalits from obtaining mental health support include financial burdens and a lack of awareness and services.

As Figure 3 illustrates, a preconception held by participants was that people with mental health conditions are ‘Pāgala’. This confirms previous findings from Brenman et al., and Kohrt and Harper. 25,26 Brenman et al., discussed how this labelling as ‘mad’ acts as a barrier in addressing mental health in Nepal. 25 Furthermore, numerous participants stated that mental health is “not a real disease” or that it is “incurable”. One participant used the word incurable to refer to how people with mental health conditions are regarded in the community, as opposed to the condition itself. This implies that once a person is categorized as ‘mentally unwell’, that their status is unrecoverable.

Several participants perceived alcohol and drugs as being interlinked with mental health and many discussed how prevalent addiction is within the community. This is supported by Kohrt et al., who highlighted the profound impact that alcoholism has on the Dalit community including domestic violence, rape, and loss of income. 10

Some interviewees discussed how mental health stigma leads to family exclusion. One participant proposed that destitution is more dangerous for women due to their increased risk of exploitation. This confirms previous knowledge whereby women are considered as ‘subordinate’ to the ‘dominant’ males in Nepal. 15

In contrast, one participant thought there was little difference in discrimination as "both genders are discriminated". This demonstrates how the impact of mental health stigma and gender varies within the Dalit community and inevitably varies based on personal experiences.

The reoccurring theme of financial hardship strengthens previous research reporting a high prevalence of poverty among Dalits. 10,14 As mentioned by previous studies, this financial burden can be a barrier to obtaining mental health support. 27 Consequently, Dalits will continue to miss out on crucial mental health support unless financial assistance is provided.

A lack of available mental health support was also identified as a barrier, as demonstrated in Figure 5. This is reinforced by the literature which emphasises the scarcity of population-wide mental health services in Nepal. 5,28

Several participants shared recommendations for tackling barriers to mental health support, which was an emerging theme. This suggests there is a willingness among Dalits for change. One such recommendation was raising awareness of mental health. This finding corroborates previous knowledge from Brenman et al., who found that awareness raising was a recurring theme for overcoming mental health barriers. 25 Notably, the two participants that suggested education as a means for overcoming barriers were the youngest and the only two Dalits from the sample to receive university education.

Religious and supernatural explanations were important causes of mental health stigma, which echoes the literature. 25 Surprisingly, the word ‘witchcraft’ was not mentioned despite its significance in a study by Brenman et al. 25 The interview findings also strengthen current knowledge that traditional and religious healers are the primary source of treatment for mental health problems in Nepal. 5 This demonstrates a need for a societal shift in the understanding of mental health.

Another significant cause of mental health stigma discussed by participants was culture. Culture is comprised of a shared system of behaviours and beliefs. 29 Therefore, there is a need for a socio-cultural transition in attitudes towards mental health in Nepal to eradicate the associated stigma. Caste-hierarchy was also examined as a cause of mental health stigma, as depicted in Figure 6. This finding corroborates research by Kohrt and Harper who concluded that the stigmatisation of mental health in Nepal is rooted in concepts linking to caste-hierarchy. 26 Of note, caste receives little consideration in global mental health literature. 10 Although the caste-hierarchy has a vast influence among Dalits, it is encouraging to see that the newer generation is shifting perceptions. This highlights how the younger generation of Dalits are challenging the hierarchy and breaking down caste-related barriers.

Additionally, a lack of mental health education was reported as a cause of stigma. This is expected considering that there is no coordinating body to supervise public education on mental health. 30

Limitations

A methodological limitation was a lack of triangulation of sources. As there was only one gatekeeper, this limited the rigour of analysis. Additionally, the sample size of both Dalits and the social workers were limited to 10 and two respectively. Initially, the intention was to interview 12 Dalits, but two social workers expressed their desire to participate and hence replaced the slots reserved for Dalits.

A key limitation was that the sample population lacked homogeneity; there was a mixture of ages, education levels and genders. Therefore, the number of interviews needed to get a reliable sense of thematic exhaustion within the data set may be larger than the number interviewed, thus reducing the likelihood of saturation. 20 Alternatively, this variability made the sample more representative of the wider community.

Respondent validation occurred with both social workers, however not with Dalits due to logistical difficulties. Another limitation was that emerging themes were not cross-checked with interviewees. This decreased the validity of the interpretation of the transcripts. Furthermore, there may have been researcher bias when coding transcripts as the researcher will have known previous findings and therefore subconsciously looked for similar findings.

Another limitation to the research procedure was the inexperience of the researcher. This may have resulted in crucial themes being overlooked. Moreover, some of the interview questions were asked based on grounded themes identified from existing literature and in some circumstances a deductive approach was used. Both of these factors may have made emerging themes more difficult to transpire.

Piloting the interview with the host proved beneficial as it became evident that certain questions needed re-phrasing to better suit the local dialect. Despite this, no pilot interview occurred with Dalits, which may have led to key questions being overlooked. Furthermore, in a few instances’ interviews were interrupted by family members walking through the room. This may have distracted the participants and influenced their answers.

Furthermore, this study only sampled participants from one Dalit community. It is important to acknowledge that there may be differences between Dalit communities, especially outside of Kathmandu, meaning findings cannot be generalised to the whole caste.

CONCLUSIONS

This study employed qualitative research methods to explore the causes and experiences of mental health stigma in the Dalit community. The interviews conducted identified that perceptions of mental health are commonly misconstrued. This leads to negative stigmatisation and consequently excludes people with mental health conditions and places them in vulnerable circumstances. Consequently, there is a need for mental health education with a focus on eradicating these negative and uninformed preconceptions. A recommendation to tackle this would be to consider introducing compulsory mental health education into the national school curricula in Nepal at secondary level by 2025. This would require commitment from the Ministry of Health/ Education. Alongside this, secondary school children should be encouraged to educate their parents on mental health to open up family discussions and dispel taboos.

Furthermore, it is crucial to help excluded community members by providing them with shelter and support, especially women at an increased risk of abuse when homeless. A recommendation to achieve this would be to consider setting up mental health safehouses in the Dalit community in Gothatar, Kathmandu. Within these safehouses, there should be affiliated mental health specialists to provide psychosocial support alongside alcohol and drug workshops to address the community’s issues with addiction.

Barriers identified that prevent Dalits from obtaining mental health support include financial burdens and a lack of awareness and services. A recommendation to combat this would be to consider training more mental health specialists including mental health nurses, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists in Kathmandu by 2025. To enable this recommendation, it is suggested that the Ministry of Health allocates funding towards mental health and that more NGOs set up mental health programs within the community.

Root-causes of mental health stigma were identified as religious and supernatural teachings, culture, caste and a lack of education. To remove these sources of stigma a societal shift in philosophy concerning the topic is required. A recommendation to achieve this could be to consider further research on the caste-system in Nepal and its impact on the mental health of Dalit communities. Findings should be used to develop a protective human rights policy to eradicate caste-based discrimination and its mediating sequelae.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to acknowledge the support of the Ric-Rose organisation for their help in data collection in Kathmandu.

Ethics: Ethics was approved by the Leeds Institute of Health Sciences Research Ethics Sub-Committee (FMHREC-18-2.3).

Funding: None.

Authorship contribution: AF is the sole author.

Competing interests: The author completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available upon request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Miss Amber Nicole French

Orchard Acre

Park Road

Plumtree Park

Nottingham

Nottinghamshire

NG12 5LX

United Kingdom

[email protected]

[email protected]

.jpg)

.jpg)