National legislation is recognized as an important tool that can directly or indirectly affect a country’s preparedness and resilience to public health emergencies. An effective and dedicated legislative framework is necessary to give effect to the obligations under Articles 5 and 13 of the International Health Regulations (IHR), and is an indicator under the Prevent pillar of the Joint External Evaluation (JEE) tool used to assess country capacity to prevent, detect and respond to public health emergencies.1,2 National legal frameworks should be effective, easily accessible to any stakeholder, and frequently reviewed, updated and assessed for consistency with the international obligations of the country.

The 2014-2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) epidemic in West Africa highlighted a number of gaps and weaknesses in the Republic of Guinea’s national public health infrastructure pertaining to the core capacities under the IHR. In the aftermath of the outbreak, and with support from international partners such as the U.S Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO), Guinea made substantial efforts to address those shortcomings by strengthening systems to prevent, detect and respond to future outbreaks and other health emergencies. A Presidential decree in July 2016 established the Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (National Health Security Agency, or ANSS), an agency of the Ministry of Health dedicated to preparedness and response to public health emergencies (hereafter “ANSS Decree (2016)”).3 Yet, in order to be effective in its role, the ANSS’ legal authorities need to be well defined and distinct from other entities involved in response to biological threats. In this context, Guinea needed to assess the authorities in place for the ANSS to act during an outbreak, including their legal and regulatory status with respect to other bodies that might be involved in a response, such as other technical ministries, the regional and prefectural government administrations, and the police force.

In 2017, Guinea participated in the JEE process.4 The JEE identified a number of specific gaps within the Guinean health security system, including with respect to Guinea’s legal and regulatory frameworks. Based on these observations, the Ministry of Health requested assistance from external partners to support a collaborative research project that would assess the legal and regulatory basis for activities related to public health emergencies preparedness and response, across all relevant government agencies and ministries. In addition to identifying references, legislation, regulations, and other legal instruments related to public health emergency management in Guinea, the project also aimed at highlighting gaps and overlaps between existing legal and regulatory documents, as well as providing evidence-based recommendations and examples of best-practices. This paper presents the results of this assessment and serves to demonstrate the utility of legislative assessment as an essential and effective tool for strengthening health security capacity.

METHODS

We combined a literature review with in-country interviews and workshops to identify and analyze legislation related to the management of public health emergencies in Guinea.

Literature review

A literature review was performed to identify references, legislation, regulations, and other legal instruments related to public health emergency management in Guinea. Searches were performed in English and French. A primary source of data was the 2016 CDC Global Health Security Agenda Country Report, which provides a preliminary map of the Guinea legal landscape pertaining to public health emergencies.5 The research team employed a “snowball” search strategy, whereby we identified references from papers and relevant legislation and followed them to identify additional data sources. Other such sources included open access databases and government websites, as well as material provided by local government officials to the research team.

The literature review also sought to identify legislative gaps, including documents that were thought to exist but could not be found (either online or in print), and were therefore not operationally relevant, as well as areas where policy or legislation was expected or required but did not exist. Once key gaps were identified and categorized, the team searched for and reviewed examples of best practices in health emergency legislation for corresponding topic areas from other countries in Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda) and Asia (Vietnam and Indonesia). This was done to provide concrete and realistic recommendations to the government of Guinea, and to identify potential global gaps. The countries were chosen because their legal frameworks share similarities with the Guinean legal system and/or they face similar constraints and challenges with respect to public health emergency management capacity building.

Stakeholder consultation

Stakeholder consultations, including a workshop held in August 2017 and in-person interviews, complemented the initial literature search. They provided an opportunity for legal and technical experts from the Guinean government and international organizations to participate in the assessment and gap analysis, and allowed us to confirm that the literature review gave an accurate overview of the legislative and regulatory framework on public health emergency management in Guinea. Interviews were conducted with the legal counsels from the Ministries of Health, Livestock, Environment, and Defense, as well as public health and emergency response experts from the Ministry of Health, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Office in Guinea. Workshop participants included all interviewees, as well as additional technical experts from the government of Guinea and the CDC.

Specifically, the stakeholder workshop on the public health emergency legislative structure of Guinea was used to validate findings from the literature review and establish a better understanding of the hierarchy of legal instruments in use in Guinea and their relevance. In small working groups, participants were introduced to two case studies describing a different public health emergency with a series of scripted injects and questions. These scenarios were used to elucidate practical steps used during emergencies and which legislative instruments are relied upon for each step of an outbreak. Participants recorded their answers on worksheets and flipcharts. Their responses were later cross-checked with existing legislative instruments.

Ethics approval

We submitted the study methods, including interview questions, to the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board (IRB). As our methods only involved collecting information from individuals in their official professional capacity, the IRB determined our study to be exempt from further review. Likewise, the Ministry of Health’s Ethical Review Board in Guinea did not require ethical approval for the conduct of the project.

RESULTS

Through literature reviews, stakeholder interviews and workshops, the team was able to analyze Guinea’s legal environment and the hierarchy between legal instruments in Guinea to:

-

identify all available legislation related to the management of public health emergencies; and

-

formulate evidence-based coordination and technical recommendations to share with Guinean government officials.

In Guinea, the team identified six national legislative codes that are of particular relevance to public health emergency management: the Public Health Code; the Code of Livestock and Animal Products; the Pastoral Code; the Code for the Protection of Wildlife and Hunting Regulation; the Water Code; and the Forest Code (Table 1).6–11

We categorized the national and subnational Guinean legislation pertaining to public health emergencies by JEE technical areas, under “Prevent”, “Detect”, “Respond” and “Other IHR-related hazards and Points of Entry (PoE)” (Table 2).

In 14 out of the 19 JEE technical areas, we identified key legislative gaps and potential areas of conflicting authorities within and between ministries. More specifically, gaps and potential areas of overlaps were observed in 5 technical areas under Prevent, 3 technical areas under Detect, 5 technical areas under Respond and 1 under "other IHR-related hazard & PoE), as further detailed in Table 3. Most consequentially, we identified a lack of formal legislation or mechanisms to support information and data sharing within and between agencies and sectors, in particular pertaining to information sharing between human health and animals health sectors in all three core JEE elements: Prevent, Detect and Respond (Table 3).

The legislative review also enabled the identification of possible gaps in corresponding foreign legislation. Most consequentially, we found no corresponding legislation in the other countries analyzed pertaining to sample sharing and transport, under Detect, and very little corresponding legislation pertaining to Respond technical areas (Table 4).12–19

DISCUSSION

The example of Guinea precisely illustrates the idea that legislative reviews are essential to ensure building health security capacity. The review highlighted the fact that the even in cases where individual agencies are provided with the mandate to lead public health emergency preparedness and response—as is the case in Guinea with the ANSS—such agencies may still be directly impacted by the legislation developed by and applicable to other government entities. Consequently, it is important to be comprehensive in identifying legislative gaps and overlaps in and between all relevant ministries and agencies.

Hierarchy between primary and secondary instruments in Guinean law

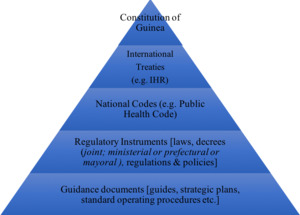

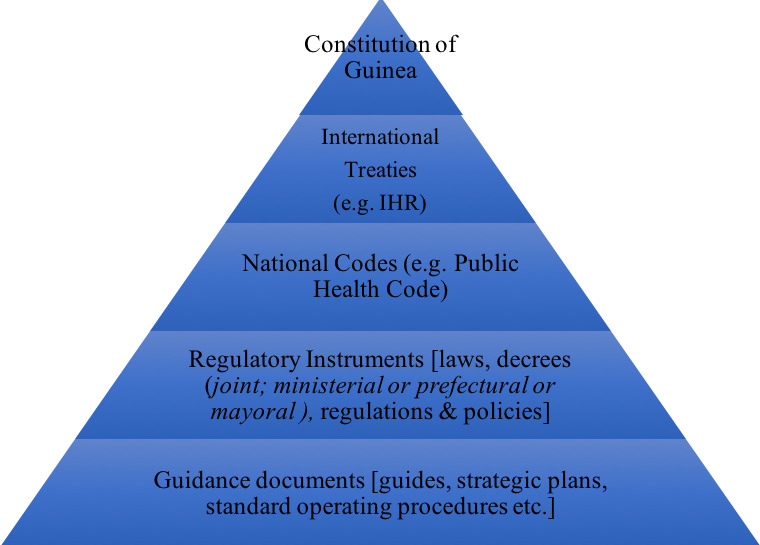

As a former French colony, Guinea draws its constitutional and legal system from the French legal tradition. The National Constitution is the supreme law of the land but is implemented both by national legislation and by international treaties. As stated in Article 151 of the Guinean Constitution, once an international treaty is approved by the National Assembly, it has authority above ordinary national laws; the hierarchical position of international treaties is higher than that of ordinary laws.20 The Guinean national legislation is codified in sector-specific codes, or grouping of laws, which are themselves implemented in detail or complemented by various regulatory instruments (Figure 1). These regulatory instruments can sometimes span different sectors or ministries, such as the One Health Platform which was created through a joint ministerial decree signed by the Minister of Health, the Minister of Livestock and the Minister of the Environment (hereafter “One Health Decree (2017)”).21 Despite clear theoretical distinctions and definitions, there does not seem to be consistency on the use of each type of instrument. The team observed that the selection of the type of regulatory instrument may therefore depend more on political or circumstantial considerations rather than a sense of legal hierarchy. Clearly, legislative analysis for the purpose of health systems strengthening must take into account these types of observed norms and practices with respect to the context of the national legal system, if the findings, and, more importantly, the recommendations, are to be effective when implemented.

Legislation related to health security

Overview

With regards to emergency preparedness and response, international agreements, such as the IHR, prevail over national law. In theory, this means that if there is a conflict between national law and provisions contained in a ratified international agreement, the latter applies. Practically, and in part due to the lack of funding available to support implementation of the IHR, this is not enforced.

In Guinea, the team identified six national legislative codes that are of particular relevance to public health emergency management: the Public Health Code; the Code of Livestock and Animal Products; the Pastoral Code; the Code for the Protection of Wildlife and Hunting Regulation; the Water Code; and the Forest Code (Table 1).6–11 While none directly conflicted with any ratified international agreements included in our analysis (for example under ECOWAS, and the IHR), the provisions in these national codes also did not comprehensively cover the full suite of technical areas required for compliance with IHR, and thus for adequate preparedness and response to potential public health emergencies.

Legislation supporting JEE indicators

For each JEE technical area, the team identified key gaps in each ministry’s legislation and highlighted potential areas of conflicting authorities within and between ministries (Table 3). For some technical areas, the team was able to identify examples of legislative documents from other countries that could be used as models to address gaps observed in the Guinean legislation (Table 4). On a broader level, this demonstrates how this type of legislative assessment may be able to have regional or even global implications, in terms of identifying priority areas for further legislative development across diverse legal systems and access to resources.

Prevent

Our assessment identified a combination of gaps and overlaps with respect to the technical areas under the “Prevent” pillar. Legislation on compliance with international frameworks and coordination is covered by the Ministry of Health and the One Health platform (2017), while the ANSS Decree (2016) describes the responsibility of the ANSS for implementing the IHR.3,21 While these instruments provide a basis for high-level decision-making relevant to health security objectives, they fail to address coordination between sub-national and national levels, as well as international cooperation. This observation echoes those from the JEE report and the GHSA gap analysis.4,5 Currently, contact with neighboring countries mostly takes place on an ad hoc and non-institutionalized basis. Instead, relevant ministries could have legislation and formal frameworks or agreements in place for cooperation and information with neighboring countries. International partners such as ECOWAS and WHO could assist Guinea in the establishment of legislation regulating international cooperation and coordination for cross-border issues. Additionally, we were unable to identify legislative mechanisms pertaining to emergency or disaster response funding mechanisms.

We observed both gaps and overlaps with respect to biosafety and biosecurity. Guinea’s legislation pertaining to this technical area is found under the authority of both the Ministry of Health and in the One Health Decree (2017), which is inherently multisectoral.6,21 While the Decree for the National Directorate for Medical Biology (2018) states that one of its responsibilities is the oversight of the application of international conventions related to biosafety and biosecurity, the One Health Decree (2017) creates a technical group responsible for ensuring that prevention efforts are strengthened across a number of areas, including biosafety.21,22 However, neither document covers national development or implementation of guidelines for acquisition, handling, management, disposal or transport of biological materials. Beyond the importance for national biosafety, this topic has profound international implications: for example, when samples need to be transported across borders for characterization or research purposes. In this case, international rcdcules on access to biological resources may provide guidance for developing national legislation, but also add a layer of complexity. Following the Ebola epidemic, the Guinean Ministry of Health took decisive steps in dealing with the biosafety and bio-security threat created by Ebola samples that remained in the country. The Ministry of Health, with support from the CDC, ensured the irradiation of its Ebola samples so that they could not inadvertently or intentionally be responsible for another outbreak. Without any legal/policy documents or memoranda of understanding in place to formalize the sharing of samples and diagnostic information between sectors and with their partners, the process to ensure adequate protections and approvals was long and time-consuming. Guinea has ratified both the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) and its Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization (2010). Those instruments introduce a comprehensive international regulation of the conditions under which Parties will share their biological and genetic resources with other Parties, as well as the equitable sharing of benefits deriving from the utilization of those resources. Even though uncertainties still remain, there is a growing consensus that pathogens fall within the scope of the Convention and Protocol. This complex legal framework is still being elaborated internationally and many Parties - Guinea included - lack dedicated implementing legislation. Guinea’s experience therefore highlights the interplay between international and national regulations when it comes to issues of public health preparedness, and the benefits that can arise from ensuring regulatory mechanisms are in place before the outbreak occurs, rather than relying on ad hoc fixes after the event. However, we were unable to find legislation from the other countries we analyzed corresponding to sample sharing and transport. While such legislation may exist outside the limited number of countries included in this assessment, it suggests that templates may be lacking, and particularly those based on codified legal systems, or for countries with limited resources.

Detect

In Guinea, the majority of legislative instruments, and the broadest coverage across sectors, was within the technical area of surveillance. It is likely that this situation is mirrored in other countries given the broad spectrum of activities surveillance encompasses. Currently in Guinea, at least four different directorates and entities within the Ministry of Health are legally responsible for aspects of planning and conducting surveillance. This includes the National Directorate for Epidemiology and Disease Control, the National Directorate for Community Health and Traditional Medicine, the ANSS, and the National Public Health Institute (INSP). Additionally, there are vertical programs for specific diseases or groups of diseases, such as vaccine-preventable diseases (PEV), HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, neglected tropical diseases, and malaria, that maintain their own surveillance activities. Finally, other ministries, notably Livestock and Environment, maintain surveillance programs for their priority pathogens and microorganisms, which sometimes also have implications for human health.

Each ministry concerned has legislation describing the steps that need to be taken upon detection of disease within their areas of oversight, including internal reporting requirements, though no single piece of legislation describes the full scope of surveillance activities. For example, the Hunting and Wildlife Protection Code (1999) states that forest service officers are authorized to cull any animal that is manifestly ill or irregularly introduced into the territory (Table 3).9 Similarly, the Public Health Code (1997) sets a mandatory reporting of infectious disease cases to relevant authorities, and the Code of Livestock and Animal Products (1995) also establishes a mandatory reporting of infectious disease cases to relevant animal health authorities.6,7 None of these codes mandates the sharing of information between ministries, however. Some coordination has been achieved through IHR implementation from the revision of Guinea’s national Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) guidelines and associated surveillance (and laboratory) tools, which have been carried out with input from the human health, animal health, and environmental sectors. However, coordination should also be codified more formally through regulation or law, both to facilitate response as well as minimize duplication of effort. While this has been achieved to some extent through the creation of the One Health Platform, which calls for ministries to share relevant disease information, the lack of requirement for the ministries themselves, via their own authorizing legislation, to share relevant surveillance data or coordinate with other sectors could undermine coordination efforts.21 The need for multisectoral mechanisms to be reinforced within each participating ministry is therefore an important detail for other countries to note when establishing their own systems for One Health at the national or sub-national level.

Respond

Perhaps most intuitively given the request for the analysis from the Guinean government, the lack of comprehensive national legislation to support emergency response was identified as a gap. Ensuring a single window for decision-making is a key tenet of emergency management. In Guinea, the Public Health Code (1997) states that only the Ministry of Health is authorized to make the declaration relating to the existence of an epidemic and to prescribe quarantine measures. In its decree, the ANSS is described as the lead agency for public health response and oversight of the public health Emergency Operations Centers.3,6 The One Health Decree (2017) also cites Emergency Operation Centers as a component of the platform’s structure; consultations with stakeholders revealed that this is in reference to the national and sub-national EOCs managed by the ANSS. However, neither the ANSS decree (2016) or the One Health Decree (2017) contain provisions on collaboration between all concerned ministries and information sharing between all actors involved in humanitarian crises response. There is no designated focal point for inter-agency cooperation or assignments of responsibilities.3,21

Similarly, while the Ebola epidemic of 2014-2016 provided insights on how police, gendarmes, and military personnel could provide assistance during epidemics, our review showed that the use of security forces in Guinea is not formalized through legislation. While some aspects of public health and security authorities is governed by the Presidency, under the Constitution (2010), and the Ministry of Defense, under The Code of Conduct for the Defense Forces (2011), neither document contains provisions on the inclusion of law enforcement agencies in health emergency response operations, particularly for joint investigation, the protection of civilian rights during security response, and the delineation of authorities between health and security officials during public health emergencies.20,23 Security challenges, including the protection of responders, have been observed in many other outbreak settings, most recently in the response to the 2018 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This illustrates the importance of formalized legislation pertaining to coordination between health and security authorities, not only in Guinea, but in any country where security may be a challenge.

Our review of the Guinean legislation pertaining to health emergencies also highlighted that risk communication, and ensuring accurate and sufficient public awareness, is an area in need of legislative clarification. While multiple pieces of legislation exist across ministries, no legislation clearly identifies the entities within the ministries responsible for risk communication. This issue is not limited to Guinea and is a particular concern in the WHO AFRO region. Indeed, WHO data shows that in 2017 43% of countries in the region had achieved less than 50% of the required attributes for risk communication under the IHR.24 Given the importance of risk communication as one of the eight core capacities under the IHR and a key technical area under Respond in the JEE, clarifying the responsibilities of pertinent ministries and agencies during epidemics should be a high priority for all countries. The most practical approach may be to develop a national communication policy for health emergencies.

We found very little corresponding legislation in the other countries analyzed relating to the Respond technical areas. Given the encouragement from the WHO for all countries to develop EOC capacity, and the known influence of insecurity and conflict on the emergence and persistence of public health events, ensuring that countries have access to useful and usable legislative templates for addressing these areas will be important.25

Other IHR-related hazards and PoE

While we identified provisions within Guinea’s Public Health code (1997) related to quarantine measures as well as criminal and penal sanctions for non-compliance, Guinea’s legislation lacks specific criteria for point of entry denials.6 The Code of Livestock and Animal Products (1995) sets outs provisions for sanitary controls at points of entry but does not address coordination with the Ministry of Health or any other sectors with respect to zoonotic or other infectious diseases.7 One limitation may be that our study did not explicitly include legislative instruments under the purview of the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which have responsibilities related to border control and immigration. This again highlights the importance of engaging sectors well outside traditional health ministries from the outset when conducting a legislative review for health security.

In Guinea, the only legislation we identified which pertained to chemical hazards was the Code of the Environment (1989), which refers to the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Environment joint decree that defines the physical, chemical, biological and bacteriological criteria of water for human consumption.26 However, it does not describe authorities for management of chemical events, and has no mention of radio-nuclear hazards. These specific hazards pose a consistent challenge for countries with respect to IHR implementation, given the explicit need to include sectors other than human health for development and oversight of policies and regulations. We were unable to identify any corresponding legislation in the countries analyzed pertaining to these technical areas. This suggests that beyond technical support for reaching compliance in these areas, legislative support may also be required to ensure sustainable and effective implementation.

Limitations

As noted in the Methods, the scope of our study included legislation across multiple sectors, and specifically engaged the Ministries of Health, Livestock, Environment, and Defense, as the primary ministries engaged in national health security capacity strengthening efforts. However, it is possible that other ministries, such as those with oversight for territorial administration, industry, and foreign affairs, may also have legislation relevant to public health emergency management, and which was not reviewed as part of this project. Even within the ministries we included, it is possible that pieces of legislation were accidentally overlooked, particularly those that may only exist in hard copy. Finally, the scope of our review of corresponding legislation was deliberately limited to a small number of countries, in order to compare with Guinea’s situation while also allowing for generalizable findings to other countries seeking to strengthen their national legislation for health security, and for these countries, our review was limited to documents in English and French. Future projects could seek to expand this scope to encompass additional countries, and provide a more comprehensive view of what legislation may exist across each of the relevant technical areas.

CONCLUSIONS

The “National Legislation, Policy, and Financing” JEE indicator under “Prevent” highlights the role of legislation and policy in IHR implementation and overall health security capacity building.2,27 Without a strong legislative and regulatory foundation, it may be challenging to secure whole-of-government support for health security capacity building, as well as to sustain it. Completing legislative reviews can therefore be considered a best practice prior to investing in new systems, infrastructures and other capacities, given that the presence of a comprehensive, effective and well-resourced legal framework that is regularly reviewed, and consistent with the international commitments of a country, is an essential component of national preparedness and response to epidemics and other health emergencies. Indeed, through laws and regulations, countries can establish norms supporting IHR core capacities and other requirements that outlast government or regimes changes.

An appropriate legislative framework is an expression of the sovereignty of a country in protecting its own population and ensuring social and political stability while respecting human rights. It provides governance and promotes internal accountability. Having mechanisms to evaluate regularly the effectiveness and appropriateness of existing laws and other regulatory instruments, and to update them, is also necessary. The legitimacy, inclusiveness, and proportionality of health measures and their underlying national legislation are crucial in ensuring their acceptance and endorsement by government workers, the population, neighboring countries, and international partners. Having adequate up-to-date laws prevents the development of conflicting secondary legislation such as decrees, ordinances, protocols, and policies. Addressing overlaps and gaps, in a way that reflects the current public health reality of the country, requires strong leadership across the different branches of government, each playing a critical role in ensuring relevant actors are at the table and determining the most appropriate legislative instrument to address a gap. Ministerial restructuring is common practice in all countries, thus undertaking a legislative landscape assessment as the one performed in Guinea can be a strategic way of assisting with governmental transitions.

Finally, many countries will have government departments and agencies that are required to work collaboratively across ministries. Legislative conflicts or gaps between and within ministries can cause confusion or a lack of clarity as to which agency has the lead. Well-written legal documents can greatly help in providing clarity and ensure a seamless coordination during emergencies, as well as improved integration of routine prevention and surveillance activities. Many countries across the globe share similar siloed vertically structured disease programs to those we observed in Guinea. Likewise, we identified a lack of formal legislation or mechanisms to facilitate and guide coordination with public health and other relevant authorities in neighboring countries, despite the benefits such mechanisms may offer for improved communication when public health emergencies threaten to cross borders. As such, the Guinean example depicted here provides lessons for other countries to break down their narrowly focused disease programs and improve intersectoral, as well as cross-border, coordination.

Developing and updating legislative documents can be a tedious and daunting task. All countries struggle with these processes. When laws are obsolete, vague, with gaps, or are overlapping, government staff may resort to using a wide range of secondary instruments and non-legal documents that may contradict the main laws and carry insufficient legislative weight to achieve the necessary objective. This problem can become magnified during emergencies when actions must be taken rapidly, are documented poorly, and must be coordinated with a wide range of other entities. Therefore, even if, a priori, there seems to be an overwhelming number of revisions needed to update national legislation for the management of public health emergencies, as we observed was the case in Guinea, an incremental approach to addressing gaps and overlaps can quickly yield benefits. For example, during our project, a number of the stakeholders noted that the process itself of engaging diverse ministries across the government was useful in raising awareness of existing laws and codes and reminding partners of each agency’s core mandate and responsibilities. Moreover, capacity-strengthening activities in key operational areas, such as diagnostics, risk communications, or workforce development, can continue to be implemented even while a supporting legislative framework is under revision or creation.

Finally, the legislative review also enabled the identification of possible gaps in corresponding foreign legislation, illustrating that this type of assessment may have larger regional or even global implications, in terms of identifying priority areas for future legislative development across diverse legal systems and access to resources.

Acknowledgements: This work would not have been possible without the close collaboration of many colleagues in Guinea, and specifically the collaboration and expertise of Dr. Sakoba Keita, Dr. Amadou Traore, M. Souleymane Toure, M. Tounkara Abdourahmane, Mme. Hadja Hawa Diallo, M. Elhadj N’Diaye Mamadou, and Prof. Sidiki Diakite. We are also very grateful for the support of Dr. Lise Martel, Mme. Binta Balde and Dr. Alpha Mahmoud Barry throughout the project. Finally, we thank Dr. Alexandra Phelan for her technical and editorial review of the draft, which substantially improved the manuscript. The authors’ state that the views expressed in the submitted article are their own and not an official position of the institution or funder. The study methods, including interview questions, were submitted to the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board (IRB). As our methods only involved collecting information from individuals in their official professional capacity, the IRB determined our study to be exempt from further review. Likewise, the Ministry of Health’s Ethical Review Board in Guinea did not require ethical approval for the conduct of the project.

Funding: This work was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement NU19GH001626).

Competing interests: The authors completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf, and declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence to:

Dr. Claire J Standley

Center for Global Health Science and Security

Georgetown University

Med-Dental Building NW306

3900 Reservoir Road NW

20007

Washington D.C

USA

[email protected]